Books of My Childhood

Homer Price

Posted 11 Jan 2017

Robert McCloskey is best known as the Caldecott-winning author/illustrator of the classic picture books Blueberries for Sal and Make Way for Ducklings, but he also wrote a series of short stories for older readers featuring a character known as Homer Price.

Homer Price was a staple of my family’s read-aloud collection. My parents must have read it to us cover to cover at least three or four times. The book was originally published in 1943, and this copy, which came from my dad’s childhood collection, is from the fourth printing, in 1966. The book remains in print to this day. That the book has stuck around for so many decades is a testament to the universal appeal of the stories.

Homer lives in the town of Centerburg, a sort of dusty Midwestern town where, as Homer puts it, “the funniest things are always happening.” And it is Centerburg, moreso than Homer himself, which becomes the protagonist of these stories. The town’s inhabitants are the primary focus of the stories, and unusually for a children’s book, most of the characters are adults: there’s the Sheriff, a comic-relief character whose speech is hopelessly mangled in spoonerisms; Dulcey Dooner, a hapless lowlife; and Uncle Ulysses, owner of the local lunchroom and a collector of gadgets. These quirky adult characters and their hopeless incompetence at dealing with Centerburg’s fiascoes are the backbone of every Homer Price tale.

Homer appears to be somewhere between the ages of eight and ten, but in practice he is the most mature character of the lot; moreso, in fact, than any of the actual adults. When robbers roll into town, it is Homer’s levelheaded thinking foils them, with no thanks to the bumbling Sheriff. When a mysterious stranger visits, it’s Homer who finds out his secret, while the adults are afraid to approach him. This structure is of course quite common in children’s fiction, but the strange thing about Homer is that even among children he tends to come across more as an adult than as a child himself. In one story, Homer’s young friend Freddy is obsessed with the comic-book exploits of “The Super-Duper.” Homer is nonplussed:

“These Super-Duper stories are all the same…he always rescues the pretty girl and catches the villain on the last page,” said Homer.

“Of course,” said Freddy. “That’s to show that crime does not pay!”

“Shucks!” said Homer. “Let’s go pitch horseshoes.”

The eventual conclusion of the story vindicates Homer’s cynical assessment of the comic, and in the end even Freddy is convinced that the Super-Duper is an unworthy idol. That Homer is at home in the world of adults is a necessary conceit in these sorts of stories, but his inability to relate to the other children makes him somewhat of an oddball character.

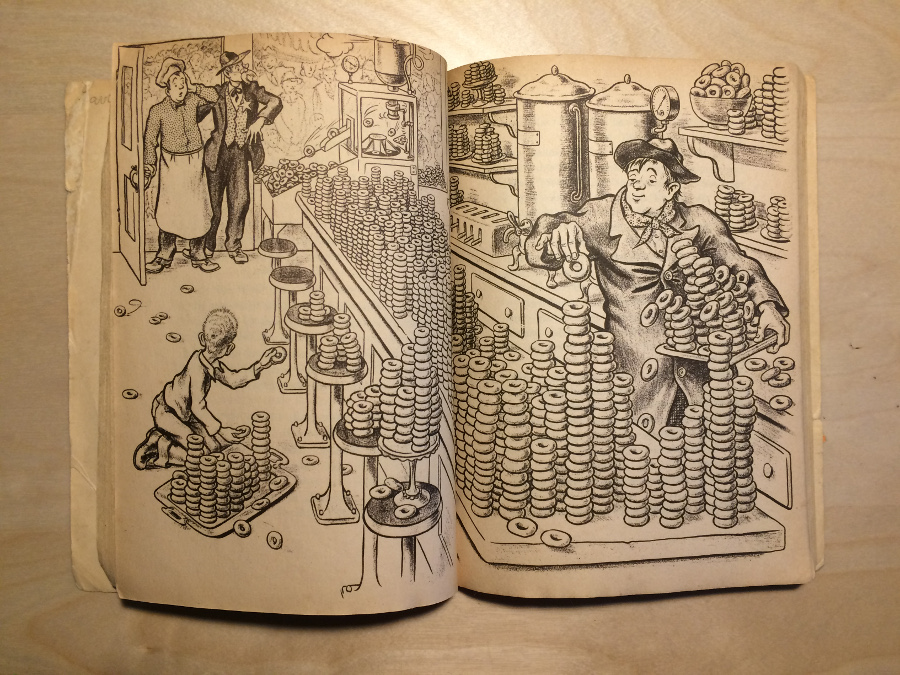

The collection’s most memorable story is probably “The Doughnuts,” in which Uncle Ulysses acquires an automatic doughnut-making machine. Ulysses leaves Homer in charge of the machine, his absence setting the stage for comedy. Soon Homer gets the machine running with the help of a friendly rich woman, but a problem quickly becomes apparent: the machine can’t be shut off. It continues producing doughnuts with a cheerful regularity that McCloskey describes with an almost Seussian lilt:

“the hot rings of batter kept right on dropping into the hot fat, and the automatic gadget kept turning them over, and the other automatic gadget kept right on giving them a little push, and the doughnuts kept right on rolling down the little chute just as regular as a clock can tick…”

Soon the lunchroom is overrun with doughnuts, a scene which McCloskey clearly enjoyed rendering. But like most of the Homer Price tales, this one isn’t complete without a narrative twist: the rich lady who mixed up the batter discovers that she’s lost a valuable bracelet, a bracelet that has now been cooked into a doughnut and must be found. It’s a perfect mix of surreal imagery, rhythmic prose, and classical storytelling techniques.

Homer Price reads like a collection of American fairy tales. The characters are archetypal but charming. The stories are whimsical and engaging. McCloskey’s illustrations are fluid and expressive, the perfect match for his writing. While the collection dates back to 1943, there’s a definite timelessness to the tales themselves. Stories of goofy adults being shown up by precocious kids will never go out of style.