You Can't Go Home Again

How Gone Home fails at every level

Posted 12 Jan 2014

There’s one thing I want to be clear on upfront: I expected to love Gone Home. It’s a game from the same traditions I hold in highest esteem: peril-free adventures, stories told through ephemera. Critical consensus was that it was phenomenal. So I was ready to explore the empty mansion; I was psyched to unravel the mystery of the family’s absence.

Suffice it to say, my high expectations were dashed and ultimately the game proved to be my greatest disappointment of the year.

Many people have played this game and enjoyed it greatly, and I don’t want to dissuade anyone from that opportunity. Indeed, if you have any interest in this type of experience, I’d encourage you to buy it, if only to encourage the creation of more projects in this vein. That being said, I do want to discuss some of the issues that led to my disappointment in the game, because I want the next adventure to be better. (To those of you who haven’t played it, be forewarned that this will contain spoilers. Scroll down to the bottom of the review if you want a quick summary of the story.)

Narrative

Gone Home is a story game, and unfortunately its story is its greatest weakness. I didn’t know what kind of story to expect from the game, and I was chagrined to discover that the game’s narrative is primarily about teenage angst. My dislike of this as a theme is something of a matter of personal taste, admittedly, but there isn’t anything groundbreaking about the way it’s handled here. We get a lot of the “mom and dad don’t get me” bit, and a lot of the “I’m an adult I can do what I want” bit. The source of all the angst is the game’s central character, Sam (the player character’s younger sister). Sam is a teenager in the throes of first love, an inherently tired trope which isn’t really altered by the fact that the object of her desire is a girl. Sam’s overdramatic, sweeping decisions (such as her ultimate decision to abandon the house and run away with Lonnie) are perhaps typical of a teenager, but are not in any way original or surprising. This is the most grievous problem with the game: from the first time the player finds one of Sam’s journal entries, the supposed mystery is replaced with a bland, predictable teenage love story.

Sam’s story is primarily driven by sentimentality (strong emotions which are not justified by the narrative), and sentimentality is a dangerous thing. A good writer must court sentimentality without actually utilizing it; naturally a story should have strong emotions in it, but strong emotions must correspond to the actual plot. Sam’s story is a very mundane one, and while naturally it seems wildly important to her, we as an audience can see that she’s wildly overreacting.

1 Also played straight is the raging thunderstorm outside. Yes, this game effectively begins with “It was a dark and stormy night.”

Yet Sam’s story is played straight,1 and her perspective is the game’s perspective, as she is the only character who’s given a voice. Sam’s “voice” comes in the form of her inexplicable spoken journal entries, which are read to the player frequently over the course of the game. There is no in-game explanation for why the player can hear Sam’s telepathic voice in her head, although the very last room in the game contains a folder full of the journal entries, a maneuver which only serves to make things even more confusing. Regardless of how they’re framed, however, the journals are intrusive and tiresome. They dispel the mystery of the game by making Sam’s story extremely explicit, and their frequency alone makes them irritating. The concept of “show, don’t tell” applies here: Sam’s story is being shown to us in the form of her belongings, but it is also being told to us in the most distracting and unambiguous way possible.

The parents’ stories are far less developed than Sam’s. We get only a minimal understanding of each of them: the father is a struggling writer, the mother is a forest ranger. Their marriage is under some degree of strain. They don’t get the full treatment like Sam does. My understanding of the parents is fairly vague, but in actuality that’s not a bad thing. It is, in fact, more what I expected from the game. While I think there could have been a bit more effort to flesh out the parents, their story is in fact told through clues, and not through explicit voiceovers as Sam’s is.

Foreshadowing is another area in which the game makes a significant blunder. There are frequent implications that the house is literally haunted. Lights flicker mysteriously and Sam claims to have succeeded in channeling the spirit of her deceased great-uncle (using such tools as a Ouija board and the ever-popular pentagram with candles). Given these details, I expected that I would eventually encounter the ghost in some form, or that he would have some degree of importance to the story overall. Eventually, though, it becomes clear that the haunting is just window dressing. The ghost never appears other than to monkey with the electricity, and as such is little more than a distraction from the game’s otherwise realistic approach. Since this is a mysterious game to begin with, it would have been completely acceptable to me to have the supernatural play a role. Instead, the game implies a supernatural element, but then fails to carry through on it. This is not how a coherent narrative should be structured.

Finally, the game should not have had an actual ending, a fade-to-black roll-credits. This is the final sign that we are not, in fact, uncovering a mystery at our own pace, but having a story fed to us piecemeal. Once the last snippet of narrative is delivered, the game declares itself complete. Sure, we can play it again if we want another chance to look around and draw our own conclusions (as is necessary to understand the parents’ story), but we’ll have to avoid touching anything of Sam’s unless we want to have her story read to us again. Gone Home was an opportunity to present a largely unexplored type of narrative, one which is a continuous voyage of discovery, and having a specific end goal (even an unannounced one) undermines that potential.

World-building and atmosphere

Since the house of Gone Home is the game’s most important asset, its world-building must be thorough, exacting, and credible. As described in the advertising pitch, we are meant to “interrogate every detail” and “open any drawer.” This is very important to note: the game’s designers specifically ask us to pay attention to even the most minute aspects of their world. I stress this because the game for the most part fails to live up to this goal. There are many details in the game which smack of laziness and lack of thought, things which if seen in a real house would seem bizarre. For example, The Greenbriar family has literally dozens of copies of the regional phone book. They have approximately one copy for every phone in the house; in some cases multiple copies are stacked on top of each other. Abundant also are empty three-ring binders, rubber-banded stacks of coupons, and generic piles of paper which cannot be examined by the player. Noteworthy also are the bookshelves which exist in many rooms of the house. Few things provide more insight into people’s personalities than examining their bookshelves (or lack thereof), but these bookshelves are treated as an afterthought. The books have generic spine textures with few visible titles, making them completely useless as indicators of character or story. The game is filled with objects like these; generic filler which has been populated from room to room without regard to credibility or potential.

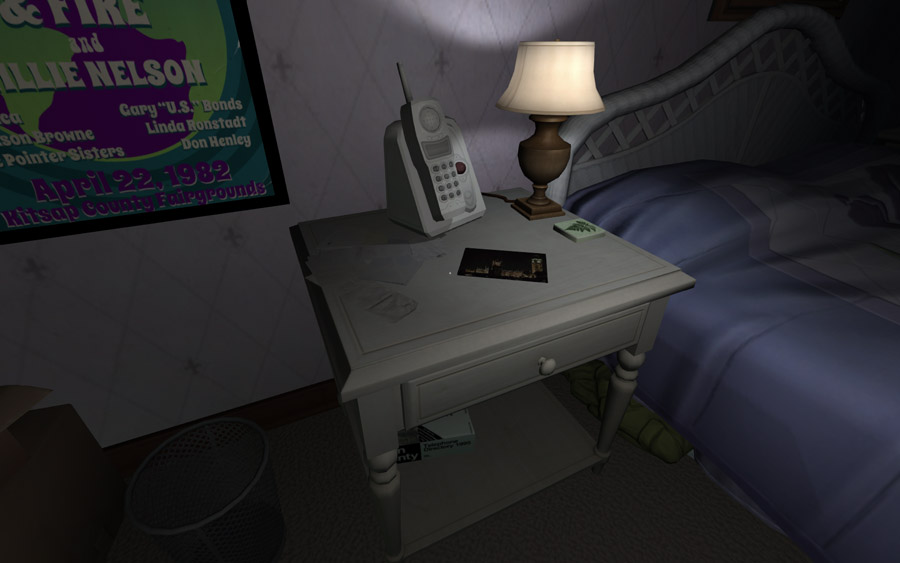

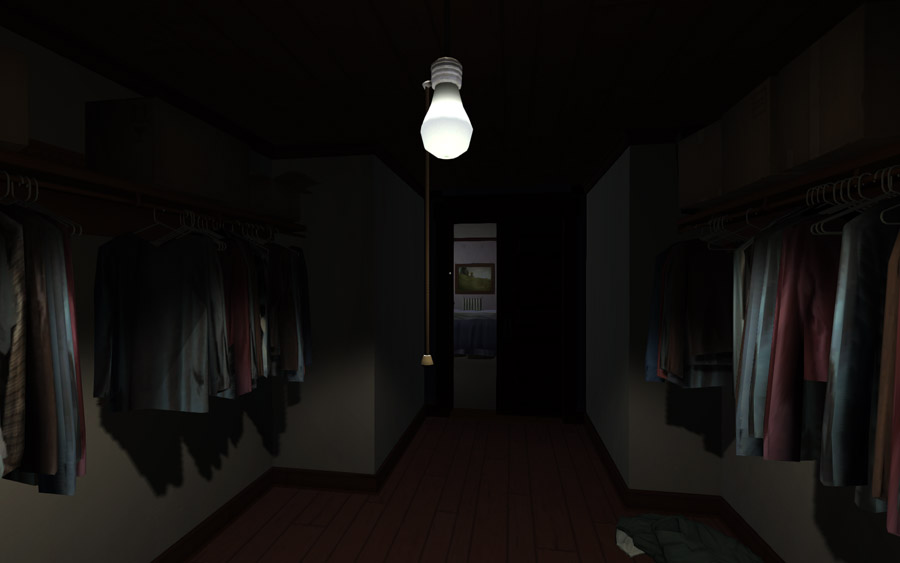

On the flip side of this, the house has conspicuous absences which cannot be explained within the confines of the game’s story. The conceit that the family has moved in only recently is a good one, waving away some of these issues, but there’s no escaping the fact that many of the drawers we’re encouraged to open are completely empty. The question I put to the developers: if you couldn’t think of anything to put in the drawer, why did you put the drawer there? Another truly bizarre oversight can be found in the parents’ closet, which contains rows of what look to be mens’ suit jackets but not a thread of women’s clothing. This is especially odd considering that the father is a freelance writer who probably wears suit jackets only rarely. Are we meant to think that the mother moved out and took all her clothes with her? If so, this is the only evidence of it, so the more probable explanation is simple corner-cutting. Admittedly, this game was created on a minimal budget, but if you’re going to invite players to invest significance in every detail, you need to make sure those details have significance.

2 Incidentally, a ghostly explanation might have made a lot of sense, had the creators decided to go that route.

Another credibility problem has to do with the placement of story-significant objects throughout the game world. Sam’s correspondences are particularly egregious in this respect. They’re full of information about her relationship with Lonnie, often information that she explicitly wants to keep secret from her parents, and yet she leaves them all over the house in conspicuous locations. The parents’ ephemera is similarly scattered; letters the father wrote and received decades earlier can be found lying out for no apparent reason. These story objects feel like the health kits and ammo of many shooter games, strewn throughout the environment without any real thought as to who put them there or why.2

3 It is possible to make a game in which players feel that they’re in danger, even if in reality they are not. By repeating frequently that there’s no danger in the game, the game’s marketers have subverted that potential.

Atmosphere is another critical element to an exploration game, and here again Gone Home comes up fairly short. The house does have an aura of mystery, yes, but not a very complex one. The raging thunderstorm, flickering lights, and darkened rooms are the primary tools used to convey this sense of eeriness, but as signifiers these are all overused to the point of cliche. Yet the game relies on these almost exclusively, so as the player becomes habituated to them the feeling of mystery eventually gives way to one of ennui, especially as the story’s banality becomes clear. Furthermore, since the game’s marketing is quite clear on the fact that the game is a danger-free experience (“non-violent”, “without getting attacked”), any sense of dread is nullified.3 Complex emotions simply don’t exist in this game; Sam’s spaces ooze with frustration and discontent at least, but most of the rooms (once “mystery” is dispelled by a flick of the light switch) don’t seem to suggest any feeling at all. The mood is, ultimately, simplistic: it depends on very tired tropes of creepiness, and the house doesn’t seem to embody any emotions other than boredom or angst.

Graphics

4 I’m tempted to say it looks like period CGI from the game’s 1990s setting, but in all honesty there’s a lot of 1990s CGI which looks a lot better than this. Toy Story, which was released the same year this game takes place, is one example.

The visuals of the game are acceptable at best, but nothing extraordinary. They’re not stylized enough to seem artistic, but not realistic enough to be invisible. Even in screenshots the plasticky quality of the game’s look is palpable. This is due to a lot of factors: textures are often bland and low-resolution, models lack realistic details, and many objects are too pristine to be believed (see for example the curtains, which are all starched-stiff and completely identical). The most critical of these factors is probably the textures, which frequently look airbrushed and blurry, and in some cases completely pixelated. As a result, the game tends to look more like lackluster CGI (which it is) rather than a believable interior space.4

Lighting is another area which this game really struggles with, and is probably a significant part of why its overall mood is so bland. The lights in Gone Home generally cast what appears to be pure white light, which in reality is fairly unusual. Most household lamps give off light in specific colors (incandescents are yellow/orange, fluorescents are greenish, LEDs are light blue, etc.), and while we tend to process these as “white,” we do notice the colors at least subliminally. Thus, the lighting in Gone Home feels somehow stale and artificial, lacking the vibrant quality of colored light that we’re more familiar with.

And, finally, a more technical point: why does this game make use of dynamic lighting, despite the fact that it contains no moving objects and only a handful of independent light sources? Having baked lightmap textures would have improved both the game performance and the game’s realism. On my machine (which while not state-of-the-art is hardly obsolete) the game had poor framerates and shadows were invariably blocky and distracting. Both of these problems could have been avoided with pre-rendered lighting. If the player isn’t going to be allowed a flashlight or some other mobile light source, there’s simply no reason to simulate lighting in real time, and the alternative would have looked a lot more attractive.

Conclusion

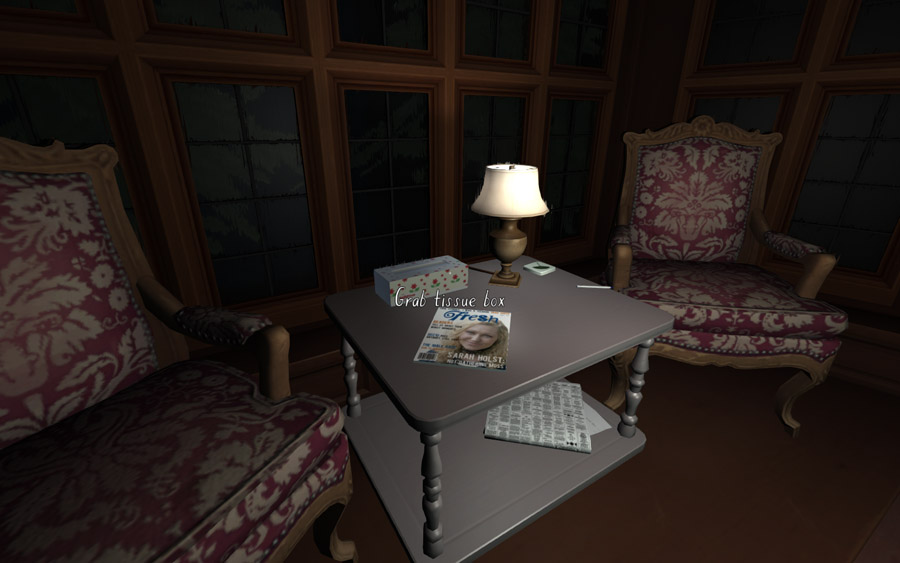

Gone Home is a good idea executed badly. Its premise is a promising one, both in terms of its fiction (where is your family?) and its gameplay (you must explore the house to find out). The experience is undone by the predictable and overwrought payoff of its story, the nonsensical construction of the environment, and the lack of artistry in its visuals. Yet in the end, much of my frustration with Gone Home is not with the game itself but with its reception. Most of the game’s critical appraisal has been focused on the same points: it’s not full of enemies, it has a story, it encourages introspection. My frustration with this kind of gushing is the implication that this is somehow novel, that Gone Home is the first of its kind. This is simply not true. In this review I’ve made a conscious effort to avoid comparing Gone Home to other games (as my primary intent has been to show that it fails to live up to its own goals), but it is worth noting that other games have tread this territory already, and done so more successfully. Quite a few people have compared Gone Home to Dear Esther, and in many cases decry the latter as being “without gameplay.” In this still-emergent medium of videogame-based narratives, it’s time to reconsider what “gameplay” means. Dear Esther eschews most of the tropes we associate with video games; the player cannot jump or climb or fight, there are no objectives to speak of, and objects can’t be picked up or interacted with in any way. Gameplay has been whittled down to two abilities: walking and looking--and that’s all it really needed. In the end, I think Gone Home’s greatest failure was its unwillingness to experiment more. It’s still trying too hard to be a Video Game in the more conventional sense, with explicit directional nudges, on-screen text overlays (”Grab Tissue Box”), an inventory, scavenger hunts, and a final objective. I wanted Gone Home to be a living, believable story space. Instead I got gameplay.

Mystery Spoiled for Your Convenience

Katie Greenbriar returns to her family’s house (which they have only recently inherited and moved into) after a trip to Europe and finds no one home. Through her explorations she learns that her parents are on a trip for their anniversary (and/or a couples’ counseling retreat) and that her sister, Sam, has been in a romantic relationship with a girl from her school, Lonnie. Sam is gone because she and Lonnie have run away together.