Books of My Childhood

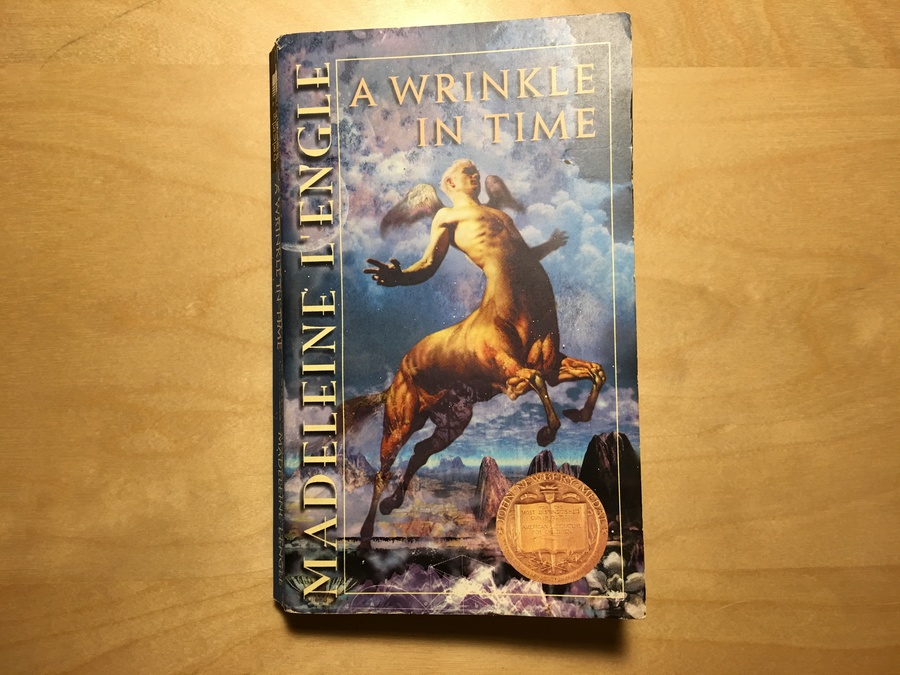

A Wrinkle in Time

Posted 04 Apr 2018

There was a period in my childhood, around the age of twelve or so I think, when A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’engle was my favorite book. In fact, it was probably the last book upon which I ever bestowed such a title, since I stopped trying to quantify my preferences around then.

As such, I had high expectations for it when I reread it, possibly too high. It’s not a bad book by any means, but it’s difficult to explain what it was that so captivated me about this novel. In many ways it’s a very skilful piece of writing, but the actual story is convoluted and vague, and the events so isolated from one another as to feel episodic. There were almost certainly books that I read simultaneously that were better constructed formally–why was this one the favorite?

My first guess is that I was drawn in by L’engle’s imagery, because she is very good at that. Rather than dumping a paragraph of description for every scene, L’engle builds her worlds with scattered details throughout the chapter, slowly bringing it into focus. The book opens with Meg, our protagonist, in her bedroom, watching a storm. Here’s what L’engle gives us:

In her attic bedroom, Margaret Murry, wrapped in an old patchwork quilt, sat on the foot of her bed and watched the trees tossing in the frenzied lashing of the wind. Behind the trees clouds scudded frantically across the sky. Every few moments the moon ripped through them, creating wraithlike shadows that raced along the ground.

The house shook.

Wrapped in her quilt, Meg shook.

A few paragraphs of introspection later, we get another glimpse of the surroundings:

The window rattled madly in the wind, and she pulled the quilt close about her. Curled up on one of her pillows, a gray fluff of kitten yawned, showing its pink tongue, tucked its head under again, and went back to sleep.

Pitch-perfect! The sudden introduction of this oblivious kitten is a wonderful bit of counterpoint against the gloom of the attic bedroom in the storm, and L’engle references it several more times in the scene. It’s such an unexpected detail, yet it fills out the world perfectly.

But quickly we return to the grim surroundings:

The wide wooden floorboards were cold against her feet. Wind blew in the crevices about the window, in spite of the protection the storm sash was supposed to offer. She could hear the wind howling in the chimneys.

We don’t just see the attic now, we hear it and feel it. Many authors do not expand the sensory range this way, but it’s really essential to creating a vivid experience for the reader.

Here is another passage, from later in the book. Notice how clipped and terse her description has become, as if to emphasize the cold and clinical nature of the setting:

They stepped into the room with the machines. In spite of the enormous width of the room it was even longer than it was wide. Perspective made the long rows of machines seem almost to meet. The children walked down the center of the room, keeping as far from the machines as possible. […] As they approached the end of the room their steps slowed. Before them was a platform. On the platform was a chair, and on the chair was a man. […] Meg stared at the man in horrified fascination. His eyes were bright and had a reddish glow. Above his head was a light, and it glowed in the same manner as the eyes, pulsing, throbbing, in steady rhythm.

It’s such a simple, but effective, passage. The eerie image of the man with the red eyes has stuck in my memory all these years, and will probably continue to do so far into the future. As the characters are catapulted across space and time, L’engle’s descriptive powers ensure that the reader is transported just as effectively.

Similarly, L’engle cultivates a very intriguing atmosphere throughout the book by referencing mysterious unnamed forces that affect each of the characters differently. Meg’s little brother, Charles Wallace, is particularly “gifted” in this area. When he is first introduced in Chapter 1, he is painted not just as a precocious child, but as one who seems to have some sort of supernatural intuition as well. Meg and her mother both comment that he seems to know things that defy explanation, and it is he who first discovers the mystical figures who will drive the plot. One particularly noteworthy moment occurs when Charles Wallace meets Meg’s friend Calvin. Calvin tells them that he frequently experiences strange compulsions that he doesn’t understand, and in this case a compulsion led him to encounter Meg and Charles in the woods. Then this happens:

Charles Wallace looked at Calvin probingly for a moment; then an almost glazed look came into his eyes, and he seemed to be thinking at him. Calvin stood very still, and waited.

Charles Wallace, apparently now reassured of Calvin’s honesty, invites him to come to dinner with them. Calvin replies:

“Well, sure, but–what would your mother say to that?” […]

“She’d be delighted. Mother’s all right. She’s not one of us. But she’s all right.”

“What about Meg?”

“Meg has it tough,” Charles Wallace said. “She’s not really one thing or another.”

“What do you mean, one of us?” Meg demanded. “What do you mean I’m not one thing or another?”

“Not now, Meg,” Charles Wallace said. “Slowly. I’ll tell you about it later.”

But he never does. The exact nature of Charles Wallace and Calvin’s abilities are never explained, let alone their source. This is not to say they are useless to the story, however. Both Charles Wallace and Calvin have opportunities to exercise their psychic powers numerous times. What’s interesting is the way L’engle incorporates them into the story. A Wrinkle in Time is filled with strange forces, and L’engle allows them to drift through the narrative like passing clouds, their influence seen briefly before dissipating into the background.

As for the plot, it’s a bit tougher to crack than I remembered. For those who haven’t read it, the gist of the book is this: Meg’s parents are both scientists, and her father has disappeared under mysterious circumstances which are presumed to be related to his research somehow. Meg wants to see him return home, but she is powerless to find him until the inexplicable appearance of a bizarre old woman who calls herself Mrs. Whatsit. Mrs. Whatsit, as it turns out, is some sort of higher being with unfathomable powers, and she whisks our characters (Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin) across the universe to track down Mr. Murry. Along the way they encounter an entity called The Black Thing, which is a manifestation of all the evil in the universe. From there it’s a hop, skip, and a jump to Mr. Murry, a series of unpleasant misadventures, and the book’s sudden, unceremonious end.

Much as I hate to admit it, the book is disjointed. The chapters tend to be strange, isolated incidents that often have little relation to those that come before and after. Mrs. Whatsit turns into a sort of flying centaur and carries the children through the air. The characters are very briefly transported to a two-dimensional planet. The gang pays a visit to an odd throwaway character called the Happy Medium. Meg is injured and has to recuperate amongst a group of benevolent, sightless aliens. These scenes are not bad by any means, but they are largely disconnected from each other. Past events may be mentioned from time to time, but they are rarely integral to the plot. A thing happens, then another thing happens. Many of the scenes could be rearranged without affecting the overall flow of the story.

The part of the book that most resembles a plot in the traditional sense doesn’t even begin until about halfway through, when the characters arrive on Camazotz, a planet under the thrall of The Black Thing. Upon arriving at the planet, Mrs. Whatsit and her companions abandon the children for reasons which are never explained (a fact which I never noticed as a kid but which bothers bothers me now). Left to fend for themselves, Meg and company enter the governmental centers of Camazotz, where Mr. Murry is imprisoned. While they look for him, though, L’engle ups the stakes for the first time in the book: Charles Wallace is hypnotized by the man with the red eyes, which effectively enslaves him. From this point onward, restoring Charles Wallace becomes the story’s main objective, especially since Mr. Murry is found and set free within a few pages of Charles’s enslavement. This twist produces plenty of strong dramatic moments, but structurally it’s a bit odd.

Another aspect of the book that merits mention is its religious undertone, which despite being fairly overt is ambiguous in its intention. It’s a far cry from the apologetics of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia books; L’engle clearly doesn’t intend for the reader to walk away from A Wrinkle in Time with a renewed commitment to Christianity. L’engle was a Christian herself, but she subscribed to the fairly unusual doctrine of universal salvation, which holds that all people will be admitted into heaven, not just Christians. In the novel L’engle expands the saved to include extraterrestrial civilizations as well, as the characters encounter a race of creatures singing a variation of Psalm 96.

But even as L’engle’s heavens rejoice, The Black Thing hangs in the background, the explicit manifestation of evil. The Black Thing is not all-powerful, though. Mrs. Whatsit tells the children that people have fought it throughout history, and with her prompting the characters are able to assemble a list of a few of the Thing’s adversaries: Jesus, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Bach, Pasteur, Curie, Einstein, Schweitzer, Gandhi, Buddha, Beethoven, Rembrandt, St. Francis, Euclid, and Copernicus. That L’engle assembled this particular cast of characters says a lot about her beliefs, which appear share more with humanism than to most strains of mainstream Christianity.

Meg ultimately has to confront the essence of The Black Thing herself when she is sent to rescue Charles Wallace from Camazotz. Her weapon, she ultimately realizes, is love. By concentrating on her love for her brother, she breaks the spell and Charles is freed from the influence of the man with red eyes. Only the power of love can match the strength of The Black Thing. And it is here that the book seems to stray dangerously into cliche. I wonder whether this trope seemed as tired in 1962 (the original year of publication) as it seems now, but the fact that it does seem painfully trite to today’s readers. Nonetheless, it didn’t bother me as a kid, so maybe it doesn’t matter either way.

The best fiction provides a lens through which we can perceive the world through the eyes of another. Sometimes this perspective is that of a fictional character, such as Holden Caulfield’s familiar worldview as presented in The Catcher in the Rye. But perhaps the most interesting stories are those that reveal the world as seen by the author. Philip K. Dick is a prominent example of the latter, and I would nominate Madelieine L’engle to those ranks as well. From what we know of her personal philosophy, A Wrinkle in Time would appear to represent the universe as she perceived it: intricate, beautiful, and divinely created, inhabited by a full spectrum of lifeforms who are menaced by evil but are not without defenses. It’s a refreshing and surprisingly unusual outlook, and perhaps that is why it resonated with me.