Books of My Childhood

Ramona

Posted 18 Aug 2018

While re-reading Beverly Cleary’s Ramona books, two questions kept coming up in my mind: What makes a book timeless? And what makes a book dated?

It’s been nearly seventy years since Ramona Geraldine Quimby’s first appearance (in Cleary’s Henry Huggins, 1950), but Cleary’s rendering of the character remains as vivid today as it was then. Moreso than practically any author I can think of, Cleary excels at capturing the experience of childhood and making it viscerally relatable. And Ramona embodies these qualities more than any of Cleary’s other characters, which is how she managed to eclipse Henry Huggins in fame despite having started out as no more than “Henry’s friend’s little sister.”

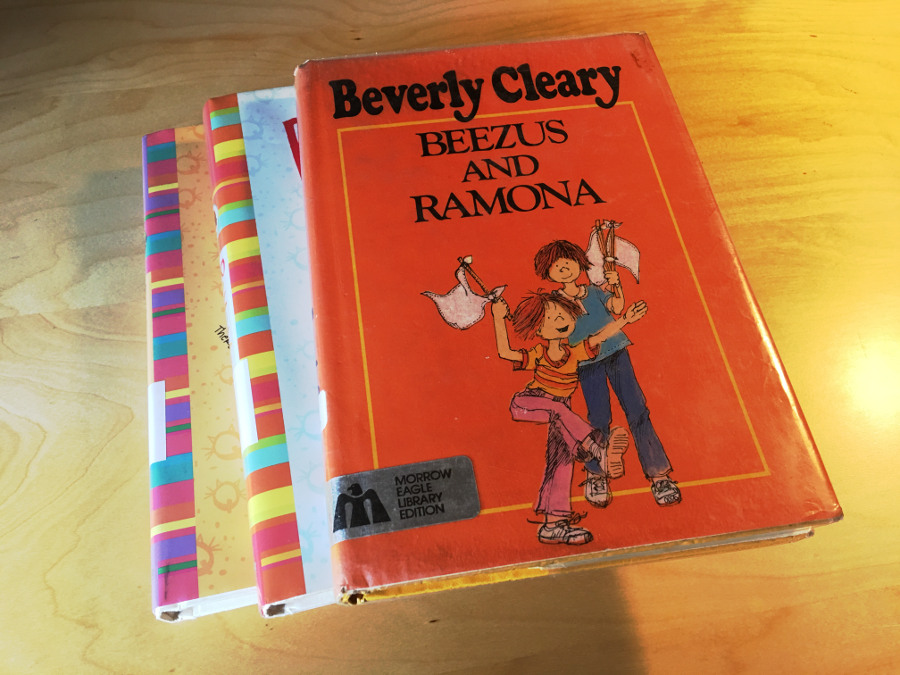

Ramona’s takeover of the spotlight began with Beezus and Ramona (1955), when she and her sister Beezus headlined a book for the first time. This book, unique in the series, is narrated from Beezus’s point of view. Yet it’s still primarily concerned with the misbehaviors of the preschool-aged Ramona. It’s also the weakest entry of the three books I read for this review. In general Cleary’s ability to evoke the emotions of her characters seems to improve as the series goes on, but this book in particular is hampered by the fact that Beezus isn’t interesting enough to carry a book on her own. The vast majority of her inner monologue consists of stewing about her irritation with Ramona. Ramona, meanwhile, does everything in her power to stoke said irritation, very effectively making this the first Ramona book rather than the sole Beezus book.

The next book, Ramona the Pest (1968), sees the characters fall into their more familiar arrangement, with Ramona taking the lead role while Beezus recedes into the background. Finally getting into Ramona’s head brings the series into its own. Where before her misbehaviors were treated like a force of nature, they can now be understood as manifestations of her situation and personality. Ramona’s desires are nothing out of the ordinary: she wants her teacher to like her, she wants respect, she wants new rain boots. Her problem is that her poor impulse control and limited understanding of the world frequently align to obstruct her goals. Cleary orchestrates Ramona’s life to magnify this effect. When Ramona gets the shiny red boots she’s coveted, her natural instinct is to take them for a test drive in the mud. Inevitably, Ramona’s feet become stuck, a tribulation that goes on for several pages. (This also gives an opportunity to show off Ramona’s theatrical imagination, as she fantasizes about being pulled from the mud by a tow truck.) Finally Ramona is wrenched from the mud by an annoyed Henry Huggins, but her boots get left behind. Ramona’s despair is palpable, a perfect evocation of that familiar childhood theme: the fun idea that lead to horrible unforseen consequences. But the story is not a tragedy: Henry reluctantly retrieves her boots a couple pages later, and Ramona is elated. This is how Cleary structures the vast majority of Ramona’s experiences, as a roller-coaster ride of emotion driven by Ramona’s own decisions. This is character-based storytelling at its finest.

Cleary likewise excels at capturing more subtle nuances of childhood, particularly in the next book, Ramona the Brave (1975). Children often impart great significance onto seemingly trivial aspects of their lives, but few authors succeed at conveying this concept, if they even remember to try. Ramona’s life is full of such things: She searches books for the words gas, motel, and burger, because they’re the only three words she’s learned to read. Her teacher wears a sweater the color of split-pea soup, which Ramona holds against her because she doesn’t like split-pea soup. Ramona is afraid to sleep in the same room with her book of wildlife photos, because it contains a creepy image of a gorilla. These sorts of details ring incredibly true, and reading this as an adult provides a simulation of childhood perception like nothing else.

Cleary’s sense of humor is also pitch-perfect. She often plays off disconnects between parents and children to great effect:

“Who will take care of me if I get sick?” [Ramona asked.]

“Howie’s grandmother,” said Mrs. Quimby. “She’s always glad to earn a little extra money.”

Ramona, who knew all about Howie’s grandmother, made up her mind to stay well.

Another example:

Howie’s mother came with his messy little sister, Willa Jean, who was the sort of child known as a toddler. Mrs. Kemp and Mrs. Quimby sat in the kitchen drinking coffee and discussing their children while Beezus and Ramona defended their possessions from Willa Jean. This was what grown-ups called playing with Willa Jean.

So where does the question of a book being dated come in? While the characters have rightfully been called “timeless,” Ramona’s universe definitely carries the hallmarks of its era. It’s a world where preschoolers play in the park without supervision, a world where the dogcatcher is only called if there are too many stray dogs on the playground. A world where there is a strong distinction between school clothes and play clothes. A world where a working mother is an anomaly. And (for my money, most bizarrely), a world in which it’s a generally-understood truth that blue eyes are less desirable than brown eyes. These are largely superficial details though. Even when I read these books as a kid, I did so with the understanding that they came from a time when things were different. There might be a couple details here and there that I didn’t understand, but that was true of pretty much any book. Children don’t need the illusion of an eternal present day in which all stories take place.

Why, then, do publishers continue to perpetuate the practice of re-illustration?

On one hand, re-illustration provides an opportunity for new illustrators to take on classic material, the appeal of which (as an illustrator) I can certainly understand. But this generally comes at the expense of the original illustrations, which are then banished to out-of-print editions and effectively fade into oblivion. No one would think about altering Cleary’s words to “modernize” the story, but for some reason the illustrator is deemed so inconsequential that she can be replaced entirely. It cheapens the art of illustration, and it’s a travesty.

But does re-illustration enhance the reading experience for today’s children? No. If anything, it makes it worse. The effect created by the new illustrations is often bizarrely disjointed, creating a hybrid universe where children live the quintessential mid-20th-century lifestyle, but look like this:

Is this somehow less confusing? Instead of taking place in a bygone age, the book now takes place in a world that has never existed at all. Fifty years from now these books will likely still be in print, but the pictures will show Ramona walking herself to school with a spiffy 2068 hairdo, Henry Huggins holding up fleets of autonomous cars while she crosses the street.

But perhaps technology can alleviate this problem even as it causes it. While a physical book can have only one set of illustrations, there is no such restriction on ebooks. Publishers ought to bundle digital editions with a suite of illustrations, enabling the reader to switch between different artists to see a variety of interpretations. It’s the ideal solution to the problem, allowing new illustrators to try their hand at the classics, old illustrators to remain visible, and readers to explore a wealth of different artists.

Revisiting Ramona was a joy. Her personality was as vibrant as I remembered, and her crises as relatable as ever. Children can see themselves in Ramona, and as adults, we can relive the experience of childhood with a vividness that few writers can convey. And after all, the only person more timeless than Ramona may be Beverly Cleary herself: she turned 102 this year.