Regarding Turkeys

Posted 28 Nov 2013

Here in America we are, by and large, removed from the actual production of food. Meat comes from neat styrofoam trays, no longer remotely resembling the animal it once was, and that’s how we’ve come to like it. When the animals are represented at all (which is unusual), they are either made cutesy or abstract: a smiling cartoon pig, a silhouette of a bull’s head.

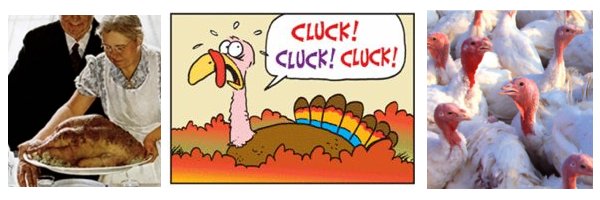

This is what makes Thanksgiving so interesting: it’s a time when American culture seems unusually aware of where the meat comes from. Turkeys have long outstripped Pilgrims as the primary icon of the holiday, and are generally depicted in one of two ways: realistic and dignified or cartoonish and manic. The realistic variety are drawn as large, healthy male specimens in enthusiastic display mode. They stare out with a sort of calm, detached dignity, willingly offering themselves up for our annual feast of gratitude. On the other end of the spectrum manic cartoon turkeys are goofy-looking creatures with bugging eyes, brown feathers, rainbow-colored tails, and tear-shaped red blobs dangling from their beaks like stray ketchup. The cartoon turkey’s primary goal in life is to not get eaten, and attempts endless cockamamie schemes to this end. This setup has been a staple of newspaper comic strips for years, which spend much of the month of November making jokes to the effect that turkeys, hilariously, are afraid of dying. This is how, in America, we show our appreciation for the animals we eat.

In actuality, the iconic, “realistic” turkey, with its lovingly-rendered feathers, is something of a fantasy creature. Some wild turkeys do indeed look like this: these are the male “gobblers,” when exhibiting their feathers to attract the (female) hens. (The hens do not engage in this behavior at all, and the gobblers do so only occasionally.) In general, turkeys are slender, diagonal creatures, walking forward with their necks outstretched like penguins leaning into a stiff wind. Wild turkeys’ feathers are generally shades of dark brown and black, resembling the burnt charcoal of a campfire. The farm-raised turkeys which make up the vast majority of Thanksgiving meals are often albino, resembling giant mutant doves. It’s also worth noting that the iconic turkey never does anything but stare dolefully out at the viewer; its stillness alone should be a tip-off of its innately fictional nature.

The cartoon turkey, comically inaccurate as it is, does get one thing right: turkeys do not want to die. In a country where pet ownership is common (only 40% of Americans report that they have no pets^), there is surprisingly little empathy for the creatures we regularly consume. The annual appearance of the shell-shocked cartoon turkey is an incredibly rare example of an animal’s fear becoming part of the American consciousness: and yet their plight is consistently depicted as laughable and moronic. The cartoon turkey’s central goal (staying alive) is depicted as a futile endeavor, a quixotic journey which will, inexorably, end at the dinner table. And yet this is exactly what these creatures actually feel, so far as anyone can know. Turkeys are timid creatures; their slow, stately walks can be quickly disrupted by sudden moves or loud noises. They panic easily, flying in all directions (and yes, they can fly) and fleeing the scene as quickly as possible. They are trying not to get eaten. This is not comical or pathetic: it’s called survival instinct, and it’s as strong in a turkey as it is in every other living creature.

So, in the spirit of Thanksgiving’s enhanced consciousness, I suggest the following exercise: use this holiday to recognize the reality of what meat is. The Thanksgiving turkey is the body of an animal. It was once alive. It could see, think, and feel pain. It had desires and memories. It avoided death to the best of its abilities, but was ultimately defeated. If it was factory-raised, it probably spent most of its life in an overcrowded barn, where it stood in excrement and depended on antibiotics to support its overwhelmed immune system. It probably never saw the sun. It probably died painfully. These are not comfortable thoughts, but to dismiss them is to shirk the responsibility of the Thanksgiving tradition.