Myst in Retrospect

The Book of Atrus

Myst barely scratched the surface of what the series was actually going to be about. Its ambiguous ending and vaguely-drawn universe left a lot of unanswered questions, and its sequel, Riven, was still years away from release. This intervening period would see the release of three tie-in novels, co-written by Rand and Robyn Miller with veteran science-fiction writer David Wingrove, who was then best-known for his future-history epic Chung Kuo. These three novels would provide a foundation of backstory upon which the rest of the series would be built.

The first of these was Myst: The Book of Atrus in 1995, which would answer many of the most pressing questions (Who is this Atrus guy, anyway? What’s D’ni?) while also setting the stage for Riven. But beyond its practical function within the narrative, it’s a decent novel in its own right as well, with compelling characters, a brisk plot, and a sweeping look at a universe that the first game had only hinted at.

The novel opens with characters we’ve never seen before, Gehn and Anna. Gehn’s wife has just died in childbirth and he’s distraught. He spurns his newborn son (Atrus, though not named at this point), storms in the direction of a volcano, and disappears. It’s a good opening: cryptic, yet still intriguing enough to get the reader’s attention. It efficiently introduces Gehn and his callous, dispassionate manner, traits which will be critically important later.

Following the prologue, the narrative skips forward a few years and properly introduces Atrus, now a young boy. He’s depicted as a precocious and intelligent child, spending his time conducting scientific experiments and exploring the desert where he lives with his grandmother, Anna. These first few chapters tend to drag, as little happens in them, but they’re necessary to establish the idyllic life that Atrus will spend the rest of the book pining for.

Anna is one of the more richly-developed characters of the series, but she doesn’t appear in any of the games, so the novels are the single greatest source of information about her. Much of Atrus’s personality was inherited from her, particularly his sense of ethics and thirst for knowledge. At this point in the book she’s depicted as intelligent and kind, but there is no indication of her own backstory or what it might entail. For the moment, she’s a nice lady who lives in the desert with her grandson.

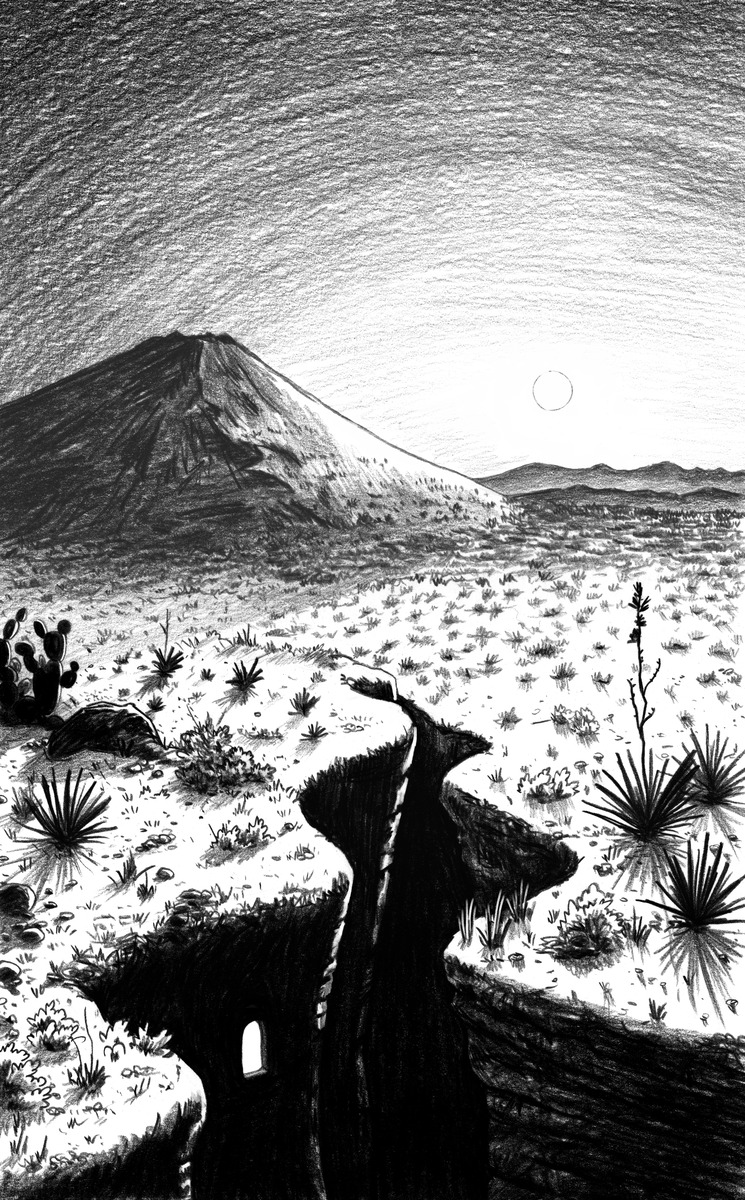

Atrus and Anna’s home is the Cleft, a large crevasse at the foot of a volcano. In the novels, it’s located somewhere in the Middle East, though when it finally appeared in the games it was relocated to New Mexico. The Cleft carries a lot of metaphorical significance, and typically means different things to different characters. To Atrus it represents a happy life which he’s been forced against his will to abandon. To Gehn, the Cleft represents a dead end, a meaningless life which he’s worked hard to escape. In the context of the Myst epic overall, the Cleft subtly echoes the form of the Star Fissure (previously seen in the Myst opening), particularly in a scene early in the book in which the flooded Cleft reflects the starry sky. In many cases the Cleft also represents humility, a theme which will recur throughout the series.

At the end of the first act of the book, Gehn emerges from the volcano (a dramatic entrance if ever there was one) and announces his intention to take Atrus to D’ni with him. The word “D’ni” is spoken only once in Myst, in reference to the room where Atrus is imprisoned, so it is here that the reader first learns what it means. D’ni is both a place and a people, the word can be used to refer either to Atrus’s ancestral race or to the underground city where they once lived.

The city of D’ni is perhaps the most significant location in the series, despite the fact that its role in Atrus-centric games is marginal at best. The D’ni were the original practitioners of the Art, and the epic and sudden collapse of their society infuses the entire series with a grim and pessimistic subtext. Our protagonists’ accomplishments pale in comparison to the grandiose legacy of their D’ni forebears, and the fact that D’ni ultimately collapsed bodes badly for their prospects. The Book of Atrus spends a fair amount of time in the ruins of D’ni, so the reader gets a strong sense of these themes, though the specifics of the Fall of D’ni are not directly discussed.

After they arrive back in D’ni, Gehn begins a campaign to educate Atrus in the ways of their ancestors. Gehn, however, was only a young child when the Fall occurred, and thus his understanding of the culture is based entirely on his vague recollections of childhood and whatever he managed to glean from exploring the ruins. Many of his beliefs aren’t even supported by evidence, but rather serve to elevate his ego and to literally deify his forebears. Elsewhere in the series, it is established that the D’ni had a taboo against equating the Art with godhood, but Gehn is under no such compunction. He is resolute in his belief that the D’ni were de facto gods, and as such, so is he – and so is Atrus. As he explains, after bringing Atrus to another Age for the first time:

“Once the D’ni ruled a million worlds[.] Now there’s only you and I, Atrus. We two, and the worlds we shall make. [...] I made this world. I made the rock on which we stand, and the very air we are breathing. I made the grass and the trees, the insects and the birds. I fashioned the flowers and the earth in which they grow. I made the mountains and the streams. All that you see, I made.”

The traditional interpretation of the Art, according to the D’ni, was that it created nothing, but rather created links to already-extant worlds matching the description composed by the writer, a concept they called the Great Tree of Possibilities. And there is significant evidence to support this, as Atrus quickly begins to notice. Atrus’s own first Age proves to have many elements he had not explicitly written in, as do Gehn’s, despite his claim to have created everything in minute detail. What’s more, the inhabitants of Gehn’s Ages invariably have memories of things that happened before Gehn ever arrived, an inconvenient fact that Gehn is not willing to discuss.

But Gehn cannot allow himself to entertain the possibility that he is not creating the worlds he visits, because his entire goal is to position himself as a god-emperor. In fact, the only reason he has any interest in Atrus is to use him to expedite this process. He quickly loses patience with Atrus’s artistic and experimental approach to Writing, eventually announcing his true intent in a crystal clear mission statement:

“I need Ages. Dozens of them! Hundreds of them! That is our task, Atrus, don’t you see? Our sacred task. To make Ages and populate them. To fill up the nothingness with worlds. Worlds we can own and govern, so that the D’ni will be great again! So that my grandsons will be lords of a million worlds!”

For a time, Atrus indulges his father’s fantasy despite not believing in it himself, but eventually his father’s shortcomings prove too significant for him to ignore. Gehn’s Ages are crude and unstable, and his attempts to fix them invariably exacerbate their problems even further. What’s more, he’s cruel, ignorant, and possibly substance-addicted. Watching this man abuse his powers to intimidate the inhabitants of his Ages eventually becomes too much for Atrus, and he attempts to flee back to the Cleft, but Gehn recaptures and imprisons him. Atrus’s only avenue of escape now is through the only Linking Book he has access to: Gehn’s Fifth Age, Riven.

Riven will be the setting of the next game, and much of the final act of the book takes place there. The Age as described in the novel is largely consistent with how it is depicted in the game, but for the most part there aren’t any specific locations from the book that also appear in the game. Perhaps it simply wasn’t possible to do so, since the game was still in development at the time. Still, to fully appreciate the Age does require a person to experience both the book and the game. In-universe, thirty years pass between the events of The Book of Atrus and the events of Riven, and only by reading the book can players understand what the Age of Riven was compared to what it becomes. One of the few locations that is clearly identifiable in both the book and the game is a giant tree, which in the book is thriving and serves as a major part of Rivenese society and ecology. In the game, it exists only as a stump – with a prison built atop it, no less. The gruesome irony of this is not directly addressed in the game, but it’s palpable to readers of the book.

On Riven, Atrus meets Katran, a young Rivenese woman and a member of Gehn’s inner circle of acolytes and apprentices. She and Atrus quickly strike up a friendship and bond over their frustrations with Gehn and their mutual interest in using the Art as a medium of self-expression. From the events of Myst, we know that the two will eventually marry, although their relationship is largely platonic for most of the book.

Katran (or Catherine, as she’s more often referred to) is likewise part of Gehn’s lord-of-a-million-worlds plan; he has taught her to Write and intends to marry her. Catherine’s facility with the Art is evident immediately: based on the unorthodox style of her Writing, Atrus believes that her Ages are physically impossible, but not only do they work, they are stable. (This is in stark contrast to Gehn’s Ages, which are rigidly structured but always on the verge of collapse.) It is from her, an outsider, that Atrus can realize the true potential of the Art.

The climax of the book’s final act revolves around Atrus and Catherine’s plot to put an end to Gehn’s conquest. Their plan is to confiscate all his Linking Books and strand him on Riven, where they presume he will be unable to practice the Art. Unable to Write any new Ages or to alter the fabric of Riven, he will lose his claim to godhood, reduced to nothing but the flawed and delusional human being that he actually is. The specifics of the plan are theatrical, perhaps needlessly so, from an in-universe perspective. What they need is a distraction, something to hold Gehn’s attention while they escape with the last of his Linking Books. They accomplish this by Writing a web of chaos into the Riven Book itself, creating volcanic chasms, the sudden appearance of giant daggers, and the Star Fissure, a gaping crack in the ground that somehow opens out into an infinite well of stars.

And it is here we finally see the narrative threads coming together to connect the events of the book to those of the first game. Catherine presents Atrus with a new Age, Myst Island, which will serve as their home after the escape from Riven. Atrus, following his final confrontation with Gehn, leaps into the Star Fissure before linking away to Myst, assuming that the book will be irretrievably lost in the abyss. The novel ends with a scene in which Atrus ruminates over these events years later, writing in his journal the familiar lines from Myst’s opening: “I realized the moment I fell into the Fissure that the book would not be destroyed as I had planned…”

As a narrative, The Book of Atrus works well; as a novel it’s decent but hardly perfect. The prose, while decent, has a trite, artificial quality that’s hard to take seriously. The characters’ dialogue is proper to a fault, like an American’s stereotype of an English person: “I hoped the trapdoor would be open, but it looks like we shall have to force our way in.” Internal monologues tend to be even more overwrought. In this passage, Atrus’s reaction to seeing something completely mundane is expressed with not one but three exclamation-marked sentences:

A girl. It was a girl. […] What in Kerath’s name was she doing? Then, with a little jolt, he understood. Washing! She was washing! That little mound beside her was a pile of sodden clothes!

The book also has many lengthy passages of description, which is not necessarily a bad thing, but the variety used here basically lists various objects and attributes, stopping somewhat short of being genuinely evocative. Granted, vibrant description is very hard to write, but in a series revolving around books of vibrant description, it would have been nice to see more of an effort made.

Despite what I’ve said, the writing style of this book, and the books that came after it, is far from bad. The plot is tightly organized, well-paced, and rarely extraneous. The characters are believable, as are their motivations. For the vast majority of readers who are not stylistic nitpickers, the prose here is more than good enough.

The Book of Atrus, as only the second Myst-related thing to be released, established that novels would play a significant part of the series – they would be no mere tie-ins but significant components of the overall narrative. Strictly speaking it’s not necessary to read the novels in order to complete the games, but the games do draw on them extensively, to their own detriment. The later games in particular tend to reference concepts from the books without making much effort to explain what they are: pity the player who enters Uru or End of Ages without having read The Book of Ti’ana.

Still, to use novels to expand the story was a particularly appropriate choice for this series, since much of the narrative was already conveyed through prose anyway. By and large, the Myst series gameplay loop consists of exploring environments, solving puzzles, and occasionally absorbing explicit story fragments from journals or cutscenes. It would have been prohibitive to try to tell three novels’ worth of story within this framework. To do so would have created a very different kind of game, one probably beyond the technology of the mid-1990s.