Myst in Retrospect

The Great Tree of Possibilities

“Take from the past only that which is good.” - Atrus

Popular culture has a remarkably short attention span, especially so in the world of video games. Talk to many video game enthusiasts and you'll get the impression that a game released five years ago is ancient history, archaic as the Model T, something their grandparents played. Many people react to these antique games with something akin to disdain, as if they were discoveries from the back of the refrigerator. This is no doubt due in part to how closely games are tied to the forward march of computer technology; it is inevitable that a game from five years ago is going to appear graphically inferior to one produced today.

That said, while games are dependent upon imperfect technologies, it is important to remember that the best games strive to transcend these limitations and excel despite them. Myst is thirty years old, placing it somewhere between Gilgamesh and Beowulf in video game years, but like any work from antiquity, it still has power and meaning worth examining. As we wrap up this journey, I want to take a final look back to consider what the Myst series accomplished, why it's important, and what its significance will be in the future.

Here's the formula: You play as a character with no name or personality beyond what you project onto it: effectively, you play as yourself. You are plunged into an unfamiliar environment, with no real understanding (at first) of the world or its characters. By exploring, you learn about the characters and their stories. Eventually you will encounter some of them, and in the end you will be asked to make a decision that will impact their lives. Along the way you will encounter obstacles which can be overcome by utilizing logic and clues found during your explorations. You are an active participant in a story. You are not the protagonist.

All the games adhere to this framework. Some of them take more liberties with it than others, and most contain additional elements that are unique to them. This structure has proven its reliability as a foundation for interactive storytelling, and luckily it’s also vague enough that it can support an infinite variety of stories, with or without Linking Books. Broad as it is, there are still a few more specific elements which need to be included to attain the unique Myst flavor.

The most obvious of these, and probably the most widely discussed, is a concept we might call "secondhand characterization." The characters of the stories, and by extension the stories themselves, are experienced not by seeing the characters directly, but by examining objects related to them. These items can be very intimate (a diary, a bed) or very public (the Gold Dome). In either case, the player meets the characters in this metaphorical sense long before encountering them in person - if you ever do.

Counterintuitively, this technique often provides a fuller knowledge of character than more traditional methods. Sirrus and Achenar, for example, come across as fairly trustworthy before their sadistic belongings reveal them as lying psychopaths. Other media use this technique as well, of course; any well-made novel or movie will include details about characters’ belongings. But what makes Myst's approach truly remarkable is that it uses this method as its primary narrative device, making dialogue and face-to-face encounters almost marginal in many cases. In most media, this technique would probably be tedious, but in an interactive space, it proves to be a remarkably strong formula. If we’re playing a game, we want to be doing something, even if it’s just rooting around in someone’s cabinets.1

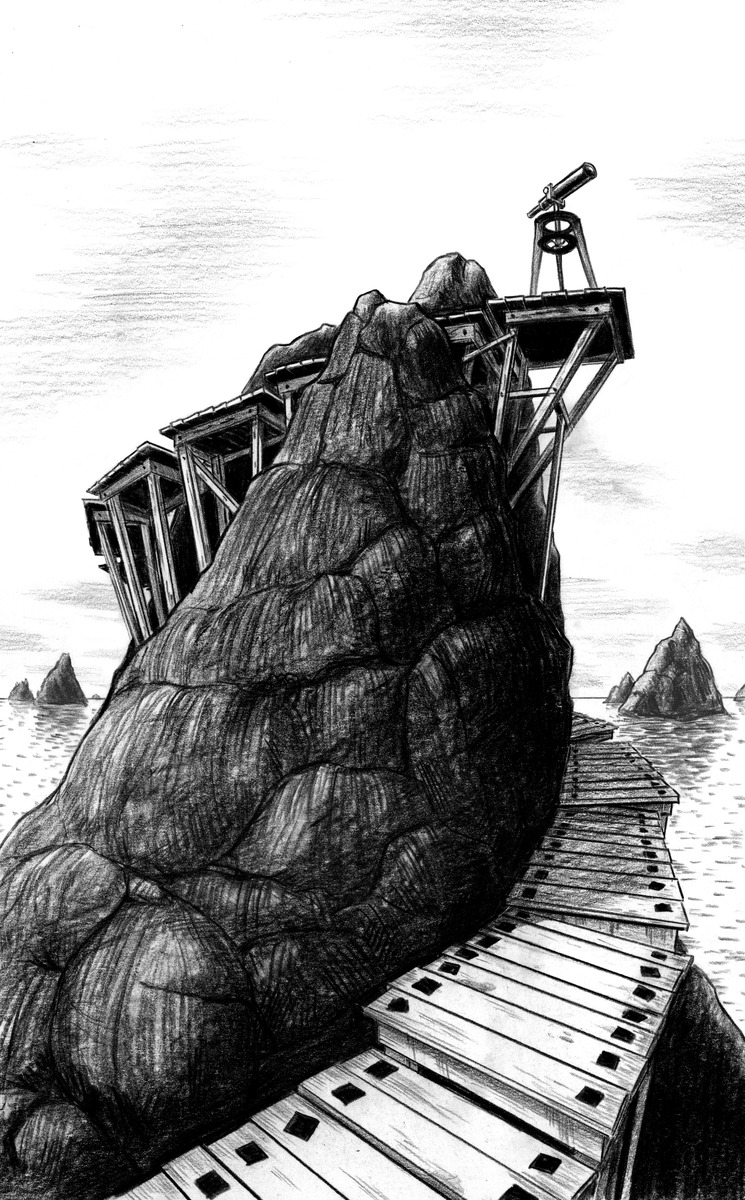

Another important device which the series employs regularly is the concept of landscape as character. Scenery in Myst is rarely presented as a simple backdrop, but rather as a complex and storied living thing with its own distinct personality. Each Age we visit has its own unique atmosphere, which both enhances player engagement and differentiates it from other Ages. While there are some similarities between, say, Channelwood and Narayan, both have many distinguishing characteristics which make them very different overall. Just as we get to know the human characters, we slowly become familiar with the traits of the worlds as well: Riven’s peculiar water, the crumbling arches of Kadish Tolesa, the glowing ore deposits of Amateria. This isn’t to say that the only differences are visual; sound, especially music, plays a strong role as well. While the first game was forced to re-use many sounds simply due to technical limitations, most of the games use unique sounds in every area, creating auditory zones that can be differentiated even if the player’s eyes are closed.2

To call the construction of these environments "level design" does them a disservice; even Cyan’s term "world assembly" seems awfully clinical. Just as the characters write Ages, the places we visit in the game are very much written, in the sense that fiction is; each one is a work of art in its own right, even divorced from any other context. Within context, of course, they are one of many elements which support the game’s overall structure, but make no mistake: in a game about exploration, success hinges almost entirely on the strength of the environments.

Equally prevalent in this series, but rarely discussed, is the concept of the player as a non-character participant. In most games, the player character, regardless of how thoroughly they’re developed, plays a central role in the events of the game, and is almost invariably the game’s protagonist. This isn’t completely true of Myst. While the player character does perform actions which further the story, the character is not developed at all (never mentioned by name anywhere), and is not included in the storyline’s drama. The player character is on the sidelines, literally pushing the switches which move the story forward, but the bulk of the narrative is backstory (which is non-participatory by definition) and character interaction (which is non-participatory in this series). The player becomes, in a way, a witness to the story, and your only ability to affect its outcome arrives in the form of the bad-ending vs. good-ending choices. (And since the bad endings aren’t canonically "real," the choice is somewhat deceptive.) Think of the series as a play in which you’re seated on stage. You can move through the set and examine it from different angles, but you’re not one of the actors, and the action will play out the same regardless of what you do. While in most of the games we play "The Stranger," the actual protagonist (or, in many cases, sympathetic villain) changes: in the first game it’s Atrus, then Gehn, Saavedro, Yeesha/Achenar, etc. The significance of this is somewhat interesting: when the player character is the protagonist, a game incorporates the player into its story to a degree which no other medium can emulate. By placing the player alongside the story, Myst is presenting itself as a more traditional sort of narrative, one in which the audience sees but does not participate in the action.

If a story is going to be based on the interactions between its characters, then naturally those characters must be fairly well-developed. In general Myst succeeds at this, particularly in the sense that it presents multiple sides of its characters. The primary way that Myst builds multifaceted characters is by introducing discrepancies between what characters say and what we find out about them elsewhere. Many of the characters are unreliable, willing to distort the truth or lie outright when it suits their purposes, but you get to know them well enough that you can not only understand that they're lying, but you can understand why they're lying. This is a large part of why Uru and End of Ages seem comparatively shallow: you don't see very many sides of their characters, so they don't in general seem very complex. For the most part, though, this series does character well, creating people who are both believable and relatable, regardless of whether you're rooting for them or against them.

Finally, the series uses puzzles as a prominent gameplay mechanic, and always attempts to disguise them as natural parts of the environment. This is sadly the area in which these games most often stumble; none of the games manage to perfectly incorporate every puzzle (although Riven comes close) and many puzzles are obvious "roadblocks" which could serve no practical function in real life. Making all the puzzles serve real-world functions is, of course, a tall order. Real life objects are generally designed to be straightforward, and so people are unlikely to design things which are overly cryptic or complicated. Coming up with an object which is plausible both as a puzzle and as a functional device isn’t easy, so I do cut the designers some slack here, especially since in most cases they do make an effort to incorporate the puzzles into the universe. Nowhere in the series can you find a puzzle that’s just a reskinned version of Mastermind or Memory.

The elements defined above are a large part of Myst's success. In many ways the series was a new kind of narrative, but in others it was a traditional narrative presented in a new way. People love stories, and they love new stories and new narrative techniques. The first Myst arrived at a time when personal computers were still something new; even by the time Riven came around many people still didn’t have computers in their homes. The novelty of personal computers created an increased demand for things to do with them, and a game which presented a clear, original story, complete with attractive imagery, easily filled that niche, and in retrospect it’s not that surprising that it sold as well as it did. This is not to cast a shadow over its strength as a work of art, which should go without saying by this point, but it is worth considering exactly why it became the original "best-selling game of all time," despite the fact that it’s often remembered as something boring or frustrating. At the simplest level, these games present a story, one which can be enjoyed without the difficult button-mashing which was more prevalent at the time, though there was (and still is) a lot of demand for that.

And what of the novels? Exactly how they fit into the grand scheme of things is somewhat unclear. By and large, knowledge of the novels is not critical to enjoyment of the games, although some details will be obscure without them. Furthermore, the novels are not great examples of novel writing in the same way that the games are examples of great game design. I would say that the most important thing to recognize in the novels is the fact that they demonstrate the innate potential of the Myst universe; that the legacy of D’ni provides a foundation for an endless number of stories, within or without the confines of video games.

So where do we go from here? Outside of remakes, it appears unlikely that Cyan, Ubisoft, or any other entity intend to make another Myst game. Likewise, the supposed fourth novel, The Book of Marrim, has been stagnant for so long I think we can safely assume that it’s kaput. The fact is, a corporate entity needs to see evidence of money to be made before they’re willing to invest in publishing something, and at this point the "Myst" name isn’t one that guarantees success. But, as we’ve established, Myst's universe still has some life left in it. There has occasionally been talk about a Myst movie or TV series, and I think there’s good potential in either. Fan creations can be a wonderful endeavor as well. The fan-directed Riven remake "Starry Expanse" appears to have been absorbed by Cyan, but there have been plenty of small fan games created over the years, and there’s always room for more. As of this writing, much of the activity in Uru Live centers around fan-made Ages. Projects like these pass the torch from the original creators to an entirely new set of artists, whose interpretations have the potential to meet or even exceed the concepts of the originals. I encourage Cyan to maintain its lenient policies on such works in the future.

But even more importantly, we should remember that the formula of Myst need not only apply to games about Linking Books. Secondhand characterization, landscape as character, the non-character participant, integrated puzzles: all of these are concepts which can be applied outside the D’ni universe, and it is here that the truly infinite nature of the formula becomes clear.

The video game sphere is saturated with titles about specific abilities: gamified simulations of war, survival, future technologies, magic, superhuman traits, et cetera. There’s a place for these games, and there are plenty of reasons to like them. It’s fun and exciting to try out Portal's teleportation device, or practice telekinesis, or take up the weapons of a master dragonslayer. We want to use this medium to do things that we can’t do in real life.

The beauty of the adventure game, however, is that it’s less about doing anything unusual, but is rather about being somewhere unusual. Portal’s story, fun as it is, exists primarily as window dressing for the main attraction: solving puzzles using the Handheld Portal Device. In a pure adventure game3, the story is the primary attraction. And if such a game is to succeed, its story must be very strong.

For the most part, Myst succeeded on this front, and should be recognized for that. Maligned as the games are by many people today, there’s a lot which can be learned from them, and a lot to be enjoyed. Its overarching storyline is likewise a complex and multifaceted thing, suitable for many more treatments. And the adventure game genre itself is undergoing something of a renaissance. Game designers are building story games again, and many of them are well worth a look for Myst fans, video game enthusiasts, and, yes, initiates from the general public. Exciting things are happening. The genre which Myst revolutionized in 1993, which had for a while seemingly died away, is coming back in force. It’s a trend which needs to be encouraged, nurtured, and contributed to. Buy these games. Talk about them. If you have the inclination, make some of your own. Yes, it’s that theme from The Book of D'ni coming back one last time: this isn’t the time to sit in the ruins of a once-proud civilization. It’s time to build a new civilization, one with worlds and stories to rival Gehn’s wildest dreams.

Footnotes

1. Of course, surreptitiously investigating the belongings of friends and relatives is an age-old pastime anyway. Myst's popularity is probably in part due to the way it taps into the desire to snoop.

2. I highly recommend closing your eyes while playing every once in a while. There’s a lot of truly remarkable sound design in these games.

3. As opposed to an action-adventure game such as Uncharted or Tomb Raider.