Myst in Retrospect

Uru: The Path of the Shell

The most common complaint about the Myst series, from the people who disliked it, is that it’s “boring.” The way these games tell their stories is unorthodox, to the point of being inaccessible to many newcomers. In the end, though, it’s the stories that make the games work. The desire to find out what happened is what pushes players to solve the puzzles. Uru’s storyline, being understated even by the standards of the series, felt somewhat empty even to invested players. This final installment, sadly, does nothing to correct that problem, and unfortunately compounds it with an almost complete lack of story and some of the most tedious and repetitive puzzles ever devised. Uru: The Path of the Shell is not without its charms, but the inescapable fact is that it is, in all honesty, pretty boring.

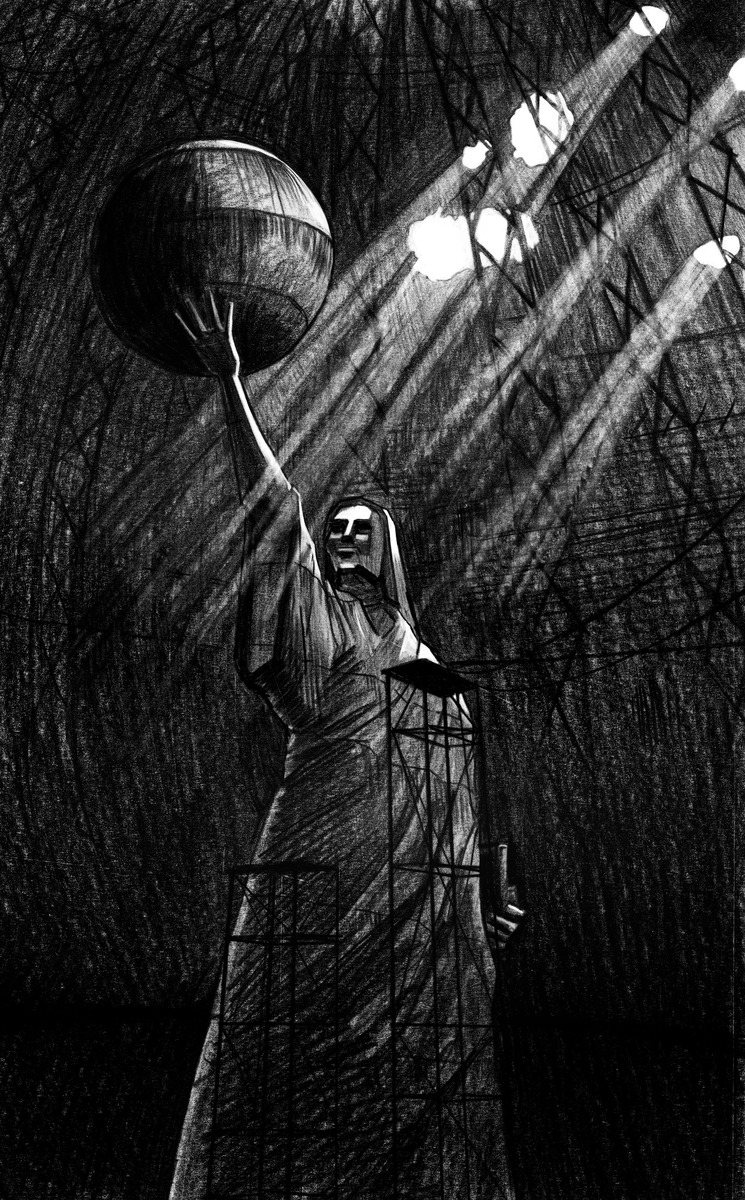

At the outset of The Path of the Shell, you gain access to a new location, the Watcher’s Sanctuary. This is an ancient D’ni shrine, named for a D’ni mystic who lived long before the Fall. The game also gives players a full set of the Watcher’s writings, which consist of Nostradamus-like cryptic ramblings that, among other things, foretell the coming of a messianic figure called The Grower. Exactly who the Grower is, and what the Grower’s destiny entails, will be the focus of the rest of the series.

There isn’t much to do in the Watcher’s Sanctuary at first: just a puzzle with no clear solution and Linking Books for two new Ages: Er’cana and Ahnonay. There’s a handy D’ni Restoration Council exposition notebook (the last of its kind, alas) which connects both Ages to our old friend Guildmaster Kadish, previously seen in Ages Beyond Myst. The notebook explains that in the final days of D’ni, Kadish had taken to styling himself as the prophesied Grower. As for the Ages, Er’cana was an agricultural Age for which Kadish designed a good deal of machinery,1 and Ahnonay was a special Age in which Kadish demonstrated the Grower’s magical time-travel abilities. (The DRC notebook remains agnostic as to the validity of these claims.) The Path of the Shell, ultimately, might be more accurately titled The Misadventures of Guildmaster Kadish.

But Kadish is dead, and the DRC has moved on. Yeesha will not be joining us. We will make this journey alone, without encountering any other characters. There are no diaries to read, no video recordings to watch. This is by far Myst’s loneliest chapter.

Moving on to the two primary Ages, let’s take a look at Er’cana. To its credit, one thing that Path of the Shell does very well in general is its striking visuals, and Er’cana is among the most dramatic environments in all of Uru. You arrive at the bottom of a narrow, sandy crevasse with smooth windswept walls, and gradually make your way out into a wider canyon which leads up to Er’cana’s industrial facility. This initial area is vast and starkly beautiful, a quiet and lonely landscape which has largely returned to the wild, and in that sense is somewhat reminiscent of Teledahn. The atmosphere is somewhat different inside the industrial complex, which is filled with a lot of noisy and very impersonal machinery.2 This is where Er’cana falls short of the example of Teledahn, though: both are functional landscapes, partially reclaimed by nature, but where Teledahn has a very distinct sense of history and Sharper’s personal perspective, most of Er’cana is just machinery. The puzzles here are fairly straightforward; most involve activating or deactivating various things in order to clear a path through the factory. The ultimate goal here is to manufacture a batch of large pellets which create light when submerged in water. These are needed later on to illuminate a cave containing an important clue.3 Of course, we’re not told why we need to make these things at first, so the only reason we know to solve the puzzles is that there’s simply nothing else to do. As in the rest of this game, there’s pretty much no story content here, which makes the explorations somewhat hollow despite the nice visuals.

Ahnonay is something entirely different. As mentioned earlier, Kadish designed Ahnonay as a place where he could demonstrate his ability to time-travel. As you explore the Age, you see the effect play out: what starts out as a tropical island suddenly becomes a stormy wasteland, and then just as suddenly seems to be floating through the void of space. We ultimately learn that the landscape we see is actually a fake, its variants contained in separate little bubbles which can be rotated into place before link-in to give the illusion that the Age is changing. The story holds that Kadish constructed this entire device in order to fool people into thinking he could travel through time, a process which involved walking around the perimeter of the Age, linking out, then linking back in to find it miraculously altered. What exactly Kadish hoped to gain by this smoke-and-mirrors demonstration is unclear.

As for Ahnonay’s puzzles, they are some of the most tedious and repetitive tasks ever brought to the video game medium. The marker hunt in To D’ni at least allows you to visit new places as you search, but Ahnonay’s puzzles tend to involve doing the same things over and over again. The first task you encounter in the Age is to chase all the crab-like “quab” creatures off of the island, a process which is cute once or twice but quickly becomes tiresome once you realize that you’re going to have to repeat it twenty or so times.4 Once that’s accomplished, you must shatter lots of crystals. From there on it’s a series of manipulations involving touching Journey Cloths at the correct intervals and swimming back and forth over lengthy distances in order to pull levers in a specific sequence. All of this must also be punctuated by frequent linking in and out of the Age, with requisite loading screens. And since none of this is spelled out explicitly, solving the Age depends entirely on trial and error. Lots of trial and error. Playing Ahnonay with a walkthrough is tedious and repetitive, but playing it without one is a serious trial of patience.5

A recurring theme in Path of the Shell is that of the passage of time, a concept which is frequently integrated into the puzzles. It’s an interesting idea, and one with a lot of potential, but in the case of this game, the temporal aspect of the puzzles primarily involves waiting. In total, you will spend a total of forty-five minutes of real-world time simply waiting for things to happen in the game, assuming that the puzzles were solved correctly. In the event that you’ve made a mistake, some of these waiting periods will need to be repeated. These forty-five minutes are broken up across three different puzzles. One is a process which takes fifteen minutes to complete, and in the interim you are free to do whatever you like. The second requires you to wait in a cave for fifteen minutes, but you’re allowed to wander around the cave while you wait. The third and most notorious is one in which standing still for fifteen minutes is the solution. I am open to games which integrate unusual mechanics and unorthodox puzzle solutions, but there’s something truly absurd about a game in which the solution to the puzzle is to leave your computer while the puzzle solves itself.6

The game’s final act is a somewhat perplexing experience. After finding and walking the Path of the Shell (which in this case is a simple labyrinth drawn on the floor), you suddenly link into the Myst Island library from the first game. The weird effect of the “you-are-you” conceit somehow makes this seem like a stunning development: the “you” character is now “really” on Myst Island, a location which the “you” character previously visited only in a video game! Never mind that the rest of the island is inaccessible, or the fact that you’re just seeing a scene from one game inside a different game. It’s an exciting moment. But you feel silly if you ask yourself why you find it exciting.

There’s not much to do in the Library, but you do have access to the fireplace and its grid-based combination lock. After entering a code gleaned piece-by-piece throughout the game, you gain access to the K’veer Linking Book from the end of the first game. After you link, a loud Yeesha voiceover cuts in. She declares herself the Grower, proclaims the Grower’s destiny as master of both time and space, and derides Kadish for his pretension. She also states that she’s liberated Kadish’s bones from his vault.

This represents the final manifestation of the reconstruction vs. rebirth dilemma, and dispels any lingering doubts about what the ultimate message of Uru is supposed to be. In fact, it’s no longer even a question: Yeesha’s path is the only remaining path, and what’s more, it’s predestined and possibly even divine. She has seemingly become immaterial, a vengeful spirit with godlike powers who will decide the course of the future whether anyone wants her to or not. “There is a new tree,” her final monologue ends. “Do you believe?”

Yet for all Yeesha’s preaching, she has never once managed to clarify exactly what she intends to do. All we know about her is her practice of subverting all the conventions we’ve come to care about, eschewing Linking Books and denigrating the D’ni legacy (and by extension, all of the events and characters of the rest of the series) while elevating the Bahro, about which we know almost nothing. If we knew Yeesha as a character, if we understood why she wants to do these things, maybe it would be easier to sympathize with her violent upending of the series. But as it is, all of Uru’s storytelling problems converge at this point. We don’t know the characters, we don’t like what they’re doing, but we’re told that what they’re doing is right.

All this brings the game to an overbearing and perplexing conclusion, raising more questions than it answers as far as The Grower’s destiny is concerned. And yet it does bring a degree of closure to the Uru storyline, which in the end seems to be a story about Yeesha’s journey to transcend the worldly remains of D’ni to become a demigod.

Her more human side gets a modicum of closure as well. Back in K’veer, she has left a message for Atrus in which she tells him that thanks to her new destiny, his “burden is lifted.” This seems to represent a sort of passing of the torch from father to daughter, and is a fairly nice character moment. Yeesha generally comes across as spiteful and dismissive of anything having to do with her father, so it’s touching to see that she actually does care about him.

There’s one more hidden ending, here, though: naturally you have to go see if Yeesha was telling the truth about Kadish’s bones, so it’s time to revisit Kadish Tolesa. But in the vault nothing appears to have changed. The skeleton is as you left it and the room is still piled high with bags of cash, carpets, and paintings of Teledahn. The inquisitive player, however, will eventually find a small Linking Book hidden in the corner. It links to an alternative version of the vault. The new vault is almost entirely empty, and Kadish’s bones are gone. You hear the musical theme of the Great Tree of Possibilities (D’ni’s metaphor for the infinite nature of the Art) and find various scraps of paper which imply that Yeesha traveled back in time and rescued Kadish from his fate. It’s a strange ending, and leaves a lot of questions unanswered (why did Yeesha save him though she otherwise seems to hate him?), but in its own understated way it’s very nice. Uru in general spends a lot of time beating you over the head with what you’re supposed to think, so it’s refreshing, for once, to be told nothing and left to form your own conclusions.

Footnotes

1. Er’cana’s relevance to the game’s story is a bit of a stretch. It seems likely that it was not originally intended to be part of the Kadish storyline, and was retroactively attached to it in the interest of getting Path of the Shell out the door.

2. The inside of the industrial complex is accessed by riding an enormous harvesting machine, an excellent Crazy Ride, and one of the few to occur in Uru.

3. This marks the second time in Uru in which you have to use awkward sources of illumination in order to see something in the dark, the first being the incredibly frustrating Eder Gira firefly puzzle in Ages Beyond Myst.

4. Another problem with the quab puzzle is that the quabs are really cute and it’s a pity to have to chase them all away.

5. It’s worth noting that the Ahnonay puzzle was designed to be played in a multiplayer environment, and was retroactively redesigned to make it work for single-player. Much of what makes it annoying in this incarnation would be rendered moot if you could delegate tasks to multiple people throughout the Age.

6. Once again, these puzzles make much more sense in a multiplayer context. Fifteen minutes of waiting wouldn’t feel so long if you were chatting with friends in the meantime, and it’s easy to imagine that a mutual reaction of “I can’t believe that worked!” could have become a fond memory for many players.