Myst in Retrospect

The Book of Ti'ana

The Myst series can be divided into two distinct parts. The installments we’ve examined so far make up what I call the “Atrus Arc,” and follow the story of Atrus and his family. The second category, the “D’ni Arc,” is focused instead on the D’ni civilization. The tie-in novel Myst: The Book of Ti’ana1 is the ideal entry point for the latter, as it is the only entry in the series which takes place in D’ni during its heyday. This is the backstory bible to rule them all, and sets the stage for the D’ni-focused games that Cyan created after the completion of Riven.

The problem with the D’ni Arc in general is that it tends to focus more on world-building than on character or plot, and as a result these installments tend to be less successful than those of the Atrus Arc. This is not to say that they are without merit. Any longtime fan will find a lot to enjoy in both The Book of Ti’ana and the games which build upon it. The Atrus Arc’s stories took place within a specific universe, and the D’ni Arc, if nothing else, strengthens that universe.

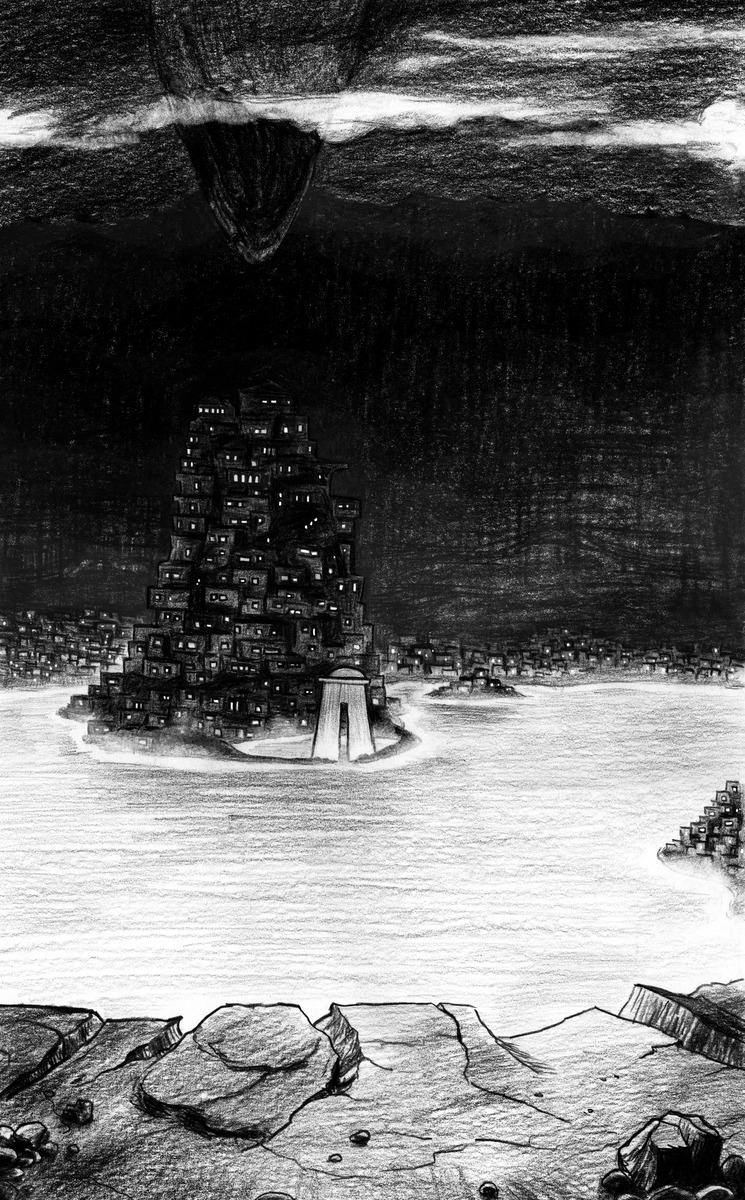

The book opens to a scene of D’ni stonecutters hard at work creating a tunnel from their subterranean city to the surface. This is a mission motivated by pure curiosity: the D’ni arrived in the Cavern via the Art, so what lies beyond it is a complete unknown. Most of the storyline at this point revolves around the fact that the completion of the tunnel is dependent on the whims of D’ni politics. While there is clearly scientific merit to finding out what lies above, many of the politicians are understandably fearful of the potential consequences of creating the tunnel, in particular the possibility of opening up the Cavern to hostile surface-dwellers. The book attempts to use these political machinations to drive the plot in the first few chapters, but it doesn’t make for compelling tension. The relevant events all occur far away from the main characters, and the reader already knows from The Book of Atrus that the tunnel was eventually completed. As such, the sixty-plus pages the book devotes to the subject are often quite tedious.

Among the workers is Aitrus, grandfather of the Atrus-without-an-“i” who we know already. Aitrus is a young guildsman, brimming with enthusiasm and the thrill of discovery. Joining him on occasion is Veovis, a lord from the Guild of Writers who seeks to befriend Aitrus for reasons which are never fully explained.2 Eventually Aitrus rescues Veovis after a tunnel collapse and their friendship is, for a time, cemented.

At the end of the first act, the expedition somehow manages to drill through all the red tape and complete their enterprise, but the government elects to seal off the tunnel without ever using it, the naysaying politicians definitively gaining the upper hand at the last second. So despite the presumably colossal expense of building the thing, the tunnel is sealed and abandoned, and Aitrus and company return to the Cavern disappointed.

Much like the events it describes, this first act is a lengthy and inconsistent thing. While it establishes two of the book’s primary characters, much of what they do is humdrum routine. They make a tunnel, they do some surveying, they make another tunnel. There is an accident and some political fallout. Work is halted, work is resumed. In one of its few breaks from this monotony we follow Aitrus on a solo expedition, but his “adventure” is arguably even less interesting, since character interaction, already pretty sparse, is rendered impossible. There’s no story here, just a lot of tunneling and boring, and boring is boring.

In the next act we cut to the surface, where we meet Anna, a young woman who lives in the desert with her father, a mineral prospector.

We follow them through daily routines for a while, then Anna’s life is thrown into disarray when her father unexpectedly dies in his sleep. Before striking out on her own, she decides to explore a tunnel they discovered earlier, which naturally turns out to be the tunnel to D’ni.

Anna manages to get all the way to the City itself, where she’s quickly apprehended. The D’ni, distraught over this violation of their precious secrecy, debate what to do with her. They won’t let her return to the surface now that she knows of their existence, so the only choices are to let her remain in D’ni or banish her to a Prison Age. Due to her intelligence and apparent lack of ill intent, she’s allowed to stay and is taken in by Aitrus’s family.

The story follows a predictable course from then on: Aitrus and Anna become friends, Aitrus reveals D’ni secrets to Anna (such as the existence of the Art), they fall in love and decide to marry. (Anna also adopts the D’ni name Ti’ana as she integrates into their society, becoming the title character.) The relationship between Aitrus and Anna drives most of the conflict in the book, as many of the D’ni (most notably Veovis) are staunchly opposed to allowing Anna to participate in society, let alone marry into it. The friendship between Aitrus and Veovis is ultimately destroyed by these tensions, and he cuts off all contact with his former friend.

If it seems like I’m glossing over these events, it’s because they’re honestly not that interesting. As in the opening, the characters are too vaguely defined to be very relatable, and much of the action follows a structure that’s downright formulaic: Aitrus and Anna do something, Veovis gets mad about it, repeat. Also, strangely, Veovis seems to be the only person who is emotionally overwrought about Aitrus and Anna’s actions. While their conduct does necessitate various court hearings and investigations, these generally lead to shrugs of acceptance on the part of everyone except Veovis, and it’s never clear why he is so much more invested than everyone else.

The relationship between Aitrus and Anna is not overly sentimental, but neither is it that original. By their proximity the reader can predict that they’re going to fall for each other, and the book never once tries to make us think otherwise. There’s no dramatic development in their relationship, no conflict between their personalities. Their only problem is the disapproval of Veovis, and so the relationship isn’t so much a story of a mutual character-building so much as it is of hero vs. villain.

The third and final act details the events surrounding the Fall of D’ni, in which Veovis plays a major part. Veovis, being the chief xenophobe in a society of xenophobes, finds Aitrus and Anna’s marriage so reprehensible that he becomes disenchanted with D’ni society itself. He confides his feelings to his friend Suahrnir, a shady character from D’ni’s police force. Suahrnir is a weird character, nurturing Veovis’s treacherous impulses for no perceptible reason. The reader never learns anything about his background, personality, or motivations. He remains a complete enigma, aiding and abetting Veovis’s crimes at all turns while never venturing from the shadows. In other parts of the series it is Veovis who is traditionally held responsible for the Fall, but as depicted here he is little more than a puppet for Suahrnir. This isn’t a bad thing, but given Suahrnir’s pivotal role, it would have been nice to get a better sense of who he is.

The final member of the triumvirate of evil is A’Gaeris, a former guildsman and convicted criminal who writes fiery political screeds. A’Gaeris is bitter about his conviction (he maintains innocence) and wants to see D’ni destroyed out of revenge. In this sense he’s developed slightly more than Suahrnir, but he still comes across as little better than a hollow vessel full of concentrated evil, driven by a desire for revenge that exceeds all reason. The only detail we get about his backstory is the fact that he carries a picture of a young woman in his journal, implicitly a lost lover/mother/sister/daughter/etc. This detail humanizes him slightly, but does nothing to explain the depth of his hatred. A’Gaeris, like Suahrnir, is a potentially interesting character, but his depiction is so vague that he never even makes sense, let alone becomes relatable.

Our three villains thus join together and plot to destroy society for reasons which are mostly unknown. Given how little we know about them, the story isn’t really about the men who cause the end of the world so much as it is about how they cause it, which is a crucial distinction. The reader watches the villains do things, but doesn’t understand their motivations or goals at all. It’s not unlike reading a report on an unfolding event, a random series of happenings without a context that explains them. The villains simply commit a series of crimes, culminating in genocide as they wipe out the D’ni population by distributing a bioweapon through the ventilation system.

No discussion of the Fall, however, can be complete without acknowledging Anna’s involvement. While the actual architects of the Fall are our three supervillains, Anna is often held responsible for it, especially by D’ni survivors. (See, for example, Esher’s comment in the final game, End of Ages: “she killed us all.”) The reasoning behind this claim is twofold: first, that by merely existing, Anna caused Veovis to become a villain. Second, that she intervened to save Veovis’s life after he was condemned to death for his crimes, thus enabling him to commit genocide later. While Anna acted in good faith, the fact remains that she was in fact the catalyst of the Fall. Her presence ultimately did destroy D’ni society, the dire predictions of the xenophobes are actually validated, which is a pretty depressing subtext.

The Book of Atrus and The Book of Ti’ana together provide most of the backstory of the series, but the two books are not equally readable. While I would argue that The Book of Atrus succeeds in being a good novel taken by itself (that is, outside of the context of the series), The Book of Ti’ana does not. It suffers from clunky pacing, extraneous subplots, and vague, undefined characters. The Book of Atrus‘s success is in no small part due to the clear motivations of its primary characters: Atrus wants to learn, and wants to return to Anna; Gehn wants to resurrect D’ni and become lord of the universe; Catherine wants to leave Riven and distance herself from Gehn; Anna wants to ensure that Atrus is safe. Note especially the ways in which the characters’ desires intersect and interfere with each other, which enables complex interpersonal dynamics. These motivations affect their actions over the course of the story, allowing character to drive the plot. As the characters in The Book of Ti’ana don’t generally have strong motivations, the plot cannot function in this manner. This is highly unfortunate, because that’s what makes a novel engaging to read.

As the first installment of the D’ni Arc, The Book of Ti’ana establishes many of the themes which will recur throughout the rest of it. Of particular note are the concepts of pride and rebirth, which are prominent in every part of the arc. These themes can likewise be extended into two dichotomies: pride vs. humility and rebirth vs. sacrifice.

Pride, and more particularly hubris, is generally depicted as the primary contributing factor of D’ni’s downfall. The concept of hubris, defined here as “presumption to challenge the gods3,” is played very deliberately throughout the book. The most explicit example of this can be found in a passage near the beginning of The Book of Ti’ana, in which Aitrus, admiring the consistent success of the massive tunneling operation, muses that the D’ni are “godlike” in their defiance of nature and adversity. The D’ni society is only protected from its own hubris by the fact that it holds humility to be a great virtue. A person who mistakes his godlike powers for literal godhood has, in their eyes, committed “the ultimate heresy.”4 Thematically the series is in agreement with the D’ni: all those who claim to be gods (such as Gehn and the Terahnee) are eventually left with nothing.

Yet the D’ni arc depicts all of D’ni society as fatally inflicted with pride. While most of the D’ni are not so far gone as to believe they are literal deities, they do fall prey to the concept that they as a people are perfect. Thus their xenophobia: why deal with outsiders, when their society is already the paragon of creation? This is particularly noticeable in the chapters immediately following Anna’s arrival, in which most of the D’ni assume her to be little more than an animal. The Fall, thematically, is more than a crime committed by a few disgruntled men: it is divine justice, the fated end for those who are blind to their own imperfections.

The Fall thus gives rise to the second dichotomy of rebirth and sacrifice. Even as the citizens of D’ni die to atone for the sins of their society, Anna and her son escape to “begin again” on the surface. Her descendants, Atrus and Yeesha, will both be critical figures in the reconstruction of post-Fall D’ni, working toward the rebirth that must arise from the sacrifice that Anna wrought.

The theme of sacrifice vs. rebirth runs throughout the D’ni Arc, particularly in the question of what to do with the ruins of the City. Characters in the D’ni Arc can be easily divided between those who see the city as an evil of the past (which should be left untouched, as a warning to future generations) or as an unfortunate loss (which should be restored). While it’s a question that’s open to discussion, the series invariably sides with the former. The question central to the D’ni Arc is whether the D’ni deserved to die, and surprisingly, the answer it provides is a resolute yes.

Footnotes

1. Like The Book of D’ni, Ti’ana was written by Rand Miller and David Wingrove, without Robyn Miller.

2. Though never clearly implied, Veovis’s interest in Aitrus could be inferred to be romantic. This would make sense in the context of his jealousy of Aitrus in later chapters. That said, I’m not sure this reading was intended by the authors. There’s not much evidence to contradict such a reading, but there’s not much to support it either.

3. D’ni is a theistic society, believing that the universe (and all possible Ages) were created by a being referred to as The Maker. It’s not clear if The Maker continues to be involved with his creation, or even if he has any special relationship with the D’ni. The various expository notebooks found in Uru make a few references to a D’ni religion and to the religiosity (or lack thereof) of various historical figures, but there is no significant information about what this religion entailed.

4. The taboo against hubris is so powerful that it’s a bridge too far even for Veovis. Despite having committed genocide, when A’Gaeris proposes that he and Veovis remake themselves as gods, Veovis is so disgusted that he prefers to die rather than be party to such a thing.